A Post By: Darren Rowse

1. Maximize your Depth of Field

While there may be times that you want to get a little more creative and experiment with narrow depth of fields in your Landscape Photography ‚Äď the normal approach is to ensure that as much of your scene is in focus as possible. The simplest way to do this is to choose a small Aperture setting (a large number) as the smaller your aperture the greater the depth of field in your shots.

Do keep in mind that smaller apertures mean less light is hitting your image sensor at any point in time so they will mean you need to compensate either by increasing your ISO or lengthening your shutter speed (or both).

PS: of course there are times when you can get some great results with a very shallow DOF in a landscape setting (see the picture of the double yellow line below).

2. Use a Tripod

As a result of the longer shutter speed that you may need to select to compensate for a small aperture you will need to find a way of ensuring your camera is completely still during the exposure. In fact even if you’re able to shoot at a fast shutter speed the practice of using a tripod can be beneficial to you. Also consider a cable or wireless shutter release mechanism for extra camera stillness.

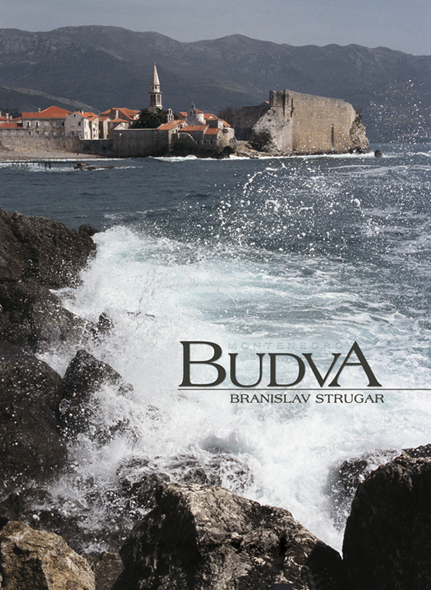

3. Look for a Focal Point

All shots need some sort of focal point to them and landscapes are no different ‚Äď in fact landscape photographs without them end up looking rather empty and will leave your viewers eye wondering through the image with nowhere to rest (and they‚Äôll generally move on quickly).

Focal points can take many forms in landscapes and could range from a building or structure, a striking tree, a boulder or rock formation, a silhouette etc.

Think not only about what the focal point is but where you place it. The rule of thirds might be useful here.

4. Think Foregrounds

One element that can set apart your landscape shots is to think carefully about the foreground of your shots and by placing points of interest in them. When you do this you give those viewing the shot a way into the image as well as creating a sense of depth in your shot.

5. Consider the Sky

Another element to consider is the sky in your landscape.

Most landscapes will either have a dominant foreground or sky ‚Äď unless you have one or the other your shot can end up being fairly boring.

If you have a bland, boring sky ‚Äď don‚Äôt let it dominate your shot and place the horizon in the upper third of your shot (however you‚Äôll want to make sure your foreground is interesting). However if the sky is filled with drama and interesting cloud formations and colors ‚Äď let it shine by placing the horizon lower.

Consider enhancing skies either in post production or with the use of filters (for example a polarizing filter can add color and contrast).

6. Lines

One of the questions to ask yourself as you take Landscape shots is ‚Äėhow am I leading the eye of those viewing this shot‚Äô? There are a number of ways of doing this (foregrounds is one) but one of the best ways into a shot is to provide viewers with lines that lead them into an image.

Lines give an image depth, scale and can be a point of interest in and of themselves by creating patterns in your shot.

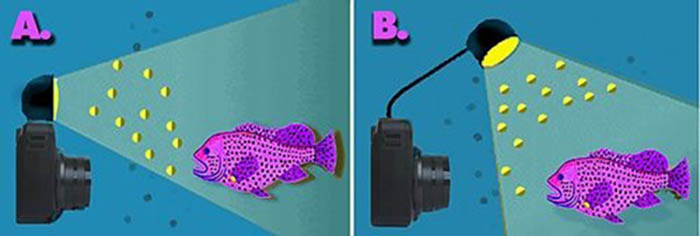

7. Capture Movement

When most people think about landscapes they think of calm, serene and passive environments ‚Äď however landscapes are rarely completely still and to convey this movement in an image will add drama, mood and create a point of interest.

Examples ‚Äď wind in trees, waves on a beach, water flowing over a waterfall, birds flying over head, moving clouds.

Capturing this movement generally means you need to look at a longer shutter speed (sometimes quite a few seconds). Of course this means more light hitting your sensor which will mean you need to either go for a small Aperture, use some sort of a filter or even shoot at the start or end of the day when there is less light.

8. Work with the Weather

A scene can change dramatically depending upon the weather at any given moment. As a result, choosing the right time to shoot is of real importance.

Many beginner photographers see a sunny day and think that it‚Äôs the best time to go out with their camera ‚Äď however an overcast day that is threatening to rain might present you with a much better opportunity to create an image with real mood and ominous overtones. Look for storms, wind, mist, dramatic clouds, sun shining through dark skies, rainbows, sunsets and sunrises etc and work with these variations in the weather rather than just waiting for the next sunny blue sky day.

9. Work the Golden Hours

I chatted with one photographer recently who told me that he never shoots during the day ‚Äď his only shooting times are around dawn and dusk ‚Äď because that‚Äôs when the light is best and he find that landscapes come alive.

These ‚Äėgolden‚Äô hours are great for landscapes for a number of reasons ‚Äď none the least of which is the ‚Äėgolden‚Äô light that it often presents us with. The other reason that I love these times is the angle of the light and how it can impact a scene ‚Äď creating interesting patterns, dimensions and textures.

10. Think about Horizons

It‚Äôs an old tip but a good one ‚Äď before you take a landscape shot always consider the horizon on two fronts.

‚ÄĘ Is it straight? ‚Äď while you can always straighten images later in post production it‚Äôs easier if you get it right in camera.

‚ÄĘ Where is it compositionally? – a compositionally natural spot for a horizon is on one of the thirds lines in an image (either the top third or the bottom one) rather than completely in the middle. Of course rules are meant to be broken ‚Äď but I find that unless it‚Äôs a very striking image that the rule of thirds usually works here.

11. Change your Point of view

You drive up to the scenic lookout, get out of the car, grab your camera, turn it on, walk up to the barrier, raise the camera to your eye, rotate left and right a little, zoom a little and take your shot before getting back in the car to go to the next scenic lookout.

We‚Äôve all done it ‚Äď however this process doesn‚Äôt generally lead to the ‚Äėwow‚Äô shot that many of us are looking for.

Take a little more time with your shots ‚Äď particularly in finding a more interesting point of view to shoot from. This might start with finding a different spot to shoot from than the scenic look out (wander down paths, look for new angles etc), could mean getting down onto the ground to shot from down low or finding a higher up vantage point to shoot from.

Explore the environment and experiment with different view points and you could find something truly unique.

Always Be Ready Unfortunately, as a landscape photographer, you don’t have the option of scheduling the perfect shot or creating the perfect lighting when you want it. You have to be willing to work with factors outside of your control and capitalize on these factors when they work in your favor. Photographs taken in the early morning hours are much different than those taken near dusk, and those beautiful thunderstorm clouds outside your window aren’t going to stick around while you decide whether or not you feel like shooting. If you want to take incredible landscape photographs, it’s a good idea to keep your gear bag packed by the door in case something interesting starts happening outside.

Be Patient Although it may seem strange that landscape photography requires grabbing an interesting shot on short notice, landscape photography actually requires a lot of patience. The moments in time captured by a landscape photographer’s lens will likely never happen again in quite the same way, so be prepared to wait for the perfect shot.

So it should be no surprise that landscape photography can be deceptively complex. It seems that all a landscape photographer would need is a camera and some nice scenery, however, a good photographer really needs a bit more. A photographer needs the right equipment, a patient mindset plus an understanding of how the time, weather and photo composition all come into play into creating an outstanding image. With those couple of things, you can start taking great landscape pictures that you’ll be proud to display on your wall.