Step 1 ‚Äď Don‚Äôt try to be perfect

It‚Äôs important to understand that there‚Äôs no such thing as ‚Äėperfect‚Äô composition. As a subjective art form, you won‚Äôt ever reach a point at which you have achieved the perfect shot, but it is possible to have poorly and well composed photographs. There are many elements to the composition of a photograph, which I‚Äôll detail as we go through, each acting as a simple guideline that will help you to take stronger and more engaging images.

Step 2 ‚Äď Simplicity

One of the main things to consider is how the elements within the shot relate to each other and therefore what you include or leave out of the shot. There is often a temptation to fill a shot with any many points of interest as possible, but when composition is concerned, it’s better to be selective about what you include in the shot and execute with consideration. Some of the most dramatic photographs have very simple but effective composition, the eye is lead into the image and the viewer can engage with a clear and effective shot.

Step 3 ‚Äď Rule of thirds

One of the simplest rules of composition is the rule of thirds, which has become an extremely common tool for amateur and professional photographers. The method involves dividing the frame into thirds, vertically and horizontally (so it actually becomes ninths), and then using those lines to effectively bisect your image, using the lines to section off areas of the image and using the nodes at which the lines cross as key areas for points of interest. This rule, although very simple, works extremely well when used effectively, for example, within a landscape shot, the horizon could cross the frame along the lower horizontal line, with the top of a mountain range crossing the upper horizontal line. Similarly, with a portrait shot, the eyes could be placed at the points at which the upper horizontal line bisects the two vertical lines.

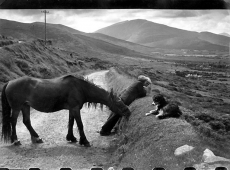

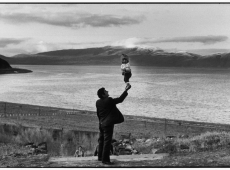

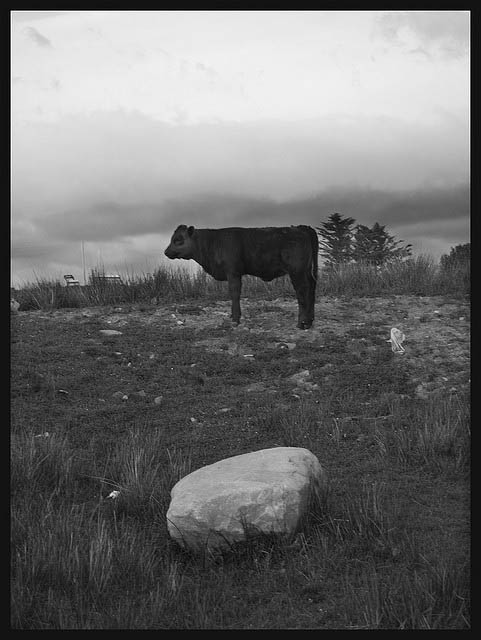

Step 4 ‚Äď Landscape Composition

Using composition effectively when working with landscapes is essential. The drama of a great landscape shot is based upon it’s composition and structure. Ask yourself what you want your shot to be about. Is it about the water, the mountains in the distance, the horizon, the sunset or the rocks in the foreground? Which elements do you want to emphasise within your shot? Using the rule of thirds, try to make sure there are layers within the image, ensure you have some foreground interest to add a sense of depth and scale within the image and that the main focal point of the shot is given priority.

Step 5 ‚Äď Lines

Lines within an image are one of the most effective ways to enhance the drama through your shot. Horizontal and vertical lines add particularly strong structure to images; where as curved lines give a more relaxed feel. Consider where each line within the images starts and leads to. It can often be very effective to have a line that leads the eye into the shot, for example, working it’s way from a bottom corner, through the image and off into the opposite back corner of the shot. Pathways, rivers, railway lines and roads will all lend themselves to this in the right situation.

When working with horizontal and vertical lines within your shots, which you undoubtedly will, please make sure that the shot is straight. You won’t believe how many shots I’ve seen that have been ruined by a slightly tilted line. Of course it is possible using post processing to correct these mistakes, but it’s far better to get into the good practice of ensuring that your shots are correctly aligned as you shoot.

Step 6 ‚Äď Shapes

Once you’ve understood the role in which line has to play within the composition of your image, you’ll be able to begin to appreciate the influence of shape as well. Try to detach yourself from looking through your viewfinder at subject matter and consider the shapes of each of the elements in the frame. It’s important to understand how the shapes interact with one another. Strong shapes such as triangles and squares will be much easier to frame than softer circular shapes, but by appreciating how each element is formed, you’ll be able to powerfully portray the shapes and their correlation as subject matter.

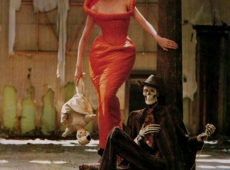

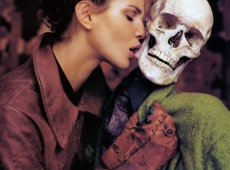

Step 7 ‚Äď Contrast within the subject matter

When approaching your subject matter, consider it in context and how it relates to it’s surroundings. How do the colours, shapes, textures and tones of the main focal point compare to that of the surrounding area? If there is strong correlation, you may be able to work with that and highlight it within the image by using composition to merge the subject within it’s context. If the subject and surroundings vary greatly, then try using compositional techniques to enhance those differences.

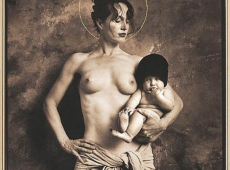

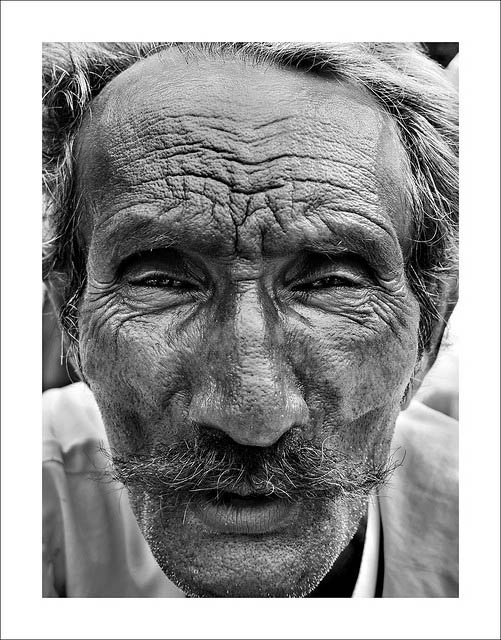

Step 8 ‚Äď Framing

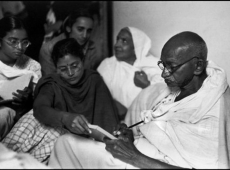

Framing a subject effectively is the basis of strong composition. The natural inclination is to put the main focal point dead centre of the frame but that can often look odd and out of context. Try offsetting the focal point either to one side or in a corner of the image to see if you can create some context for the image. Having said this, it is often the case that portraits are most dramatic when the subject is centered. so it’s up to you to experiment, but don’t just make one decision about the framing and stick with it, explore your options.

Photo by Neil Singapore

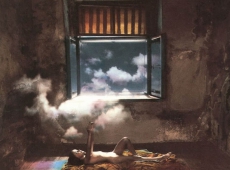

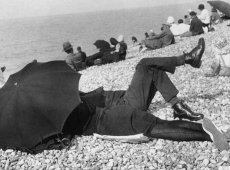

Step 9 ‚Äď Negative space

It’s important to consider the negative space within an image. When working with smaller objects, the tendency is to try and fit the whole of the focal point into the shot. In actual fact, the composition of a macro subject is far more dramatic if you either fill the frame with the subject, getting right up close, or you employ some negative space around the image to let it breath and sit within the space around it. Try experimenting with something simple like a sea shell or a watch to see how you can vary the composition, rather than just shooting it, try getting up close or giving it some space.

Photo by Armando Maynez

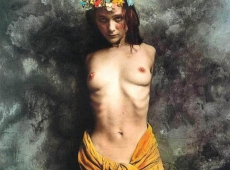

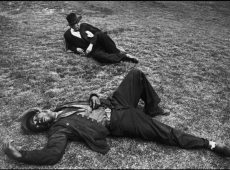

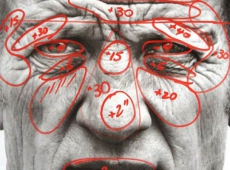

Step 10 ‚Äď Angle

When working with your subject, consider the angle at which you are shooting from. It’s often easiest to photograph as subject from the angle at which we’d usually approach it, but as you spend time with the subject, explore a variety of angles and approaches. You may well find a more interesting way to express the subject.

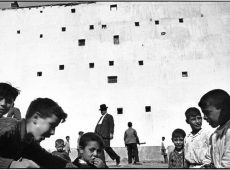

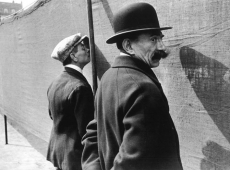

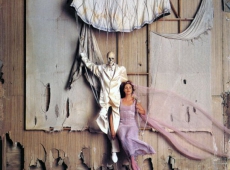

Step 11 ‚Äď Layering

Similarly to working with layers in landscape shots, don’t forget to include some element of depth within your images. Using foreground interest is the easiest way to do this, but even using staggered subject matter will add a sense of depth and lead the eye into the shot.

Photo by Simon Bray

Step 12 ‚Äď Symmetry & Pattern

The effective exploitation of symmetry and pattern can make for an extremely powerful shot, particularly when working with subjects such as architecture. Take time to observe the subject and recognise patterns (using the shapes and lines). Find the midpoint and be careful to set up the camera so it is square to the subject. Avoid external distractions that spoil the symmetry or pattern so you maximise the effect.

Photo by Simon Bray

Step 13 ‚Äď Cropping

In this age of post-processing, all is not lost if you get home and you find that you’ve not composed one of your shots how you’d like. Pretty much all edit suites now have a crop facility in which you can shave sections off shots. You can either do this with a locked ratio (most photographs are 3:2), or you can freely crop the shot into any shape you like, for example, crop to a square shot, or create a panoramic landscape shot by cropping the upper and lower levels.

Step 14 ‚Äď Practice Practice Practice

So there we have it, a set of compositional guidelines that should really help you on your way to stronger and more engaging images. As soon as you get the chance, head out and practice these suggestions. Whatever your shooting, landscapes, portraits, macro work, there is always space to try and enhance your composition to make the shot just that tiny bit more dramatic.

Please remember though, that these are not hard and fast rules to taking great shots. They may well help you, but they are also there to be broken. Once you think you’ve understood how to effectively put these into practice, feel free to start breaking them and capture your subjects in the creative way that suits you best.